Remote-controlled flight has never been easier, Schulman said, or safer – which might explain why so many are pushing the boundaries of what you can do with a drone.

One inadvertent pioneer, Raphael Pirker, was fined more than $10,000 for shooting aerial video for the University of Virginia. Pirker’s sin? He did it for money. Under FAA regulations, UAS pilots flying for commercial purposes require FAA authorization.

Pirker didn’t believe his RiteWing Zephyr II, a radio-controlled flying wing, qualified as an “aircraft.” To argue his case, he hired Schulman, then an attorney at New York City-based Kramer Levin Naftalis & Frankel, where he litigated tech cases.

“I’ve always been interested in the intersection of law and tech,” said Schulman, a graduate of Yale and Harvard Law School.

It was the first time the FAA had tried to enforce its UAS regulations, and in May 2014, it lost. The FAA had to settle for a $1,100 fee, and Schulman earned his nickname.

In a second case, Schulman defended Texas-based search-and-rescue nonprofit EquuSearch, which uses UAS to search for missing persons, after the group got a warning email written from an FAA regulator. Schulman took the issue to U.S. District Court in D.C., where a judge ruled the email did not “represent the consummation of the agency’s decision-making process.”

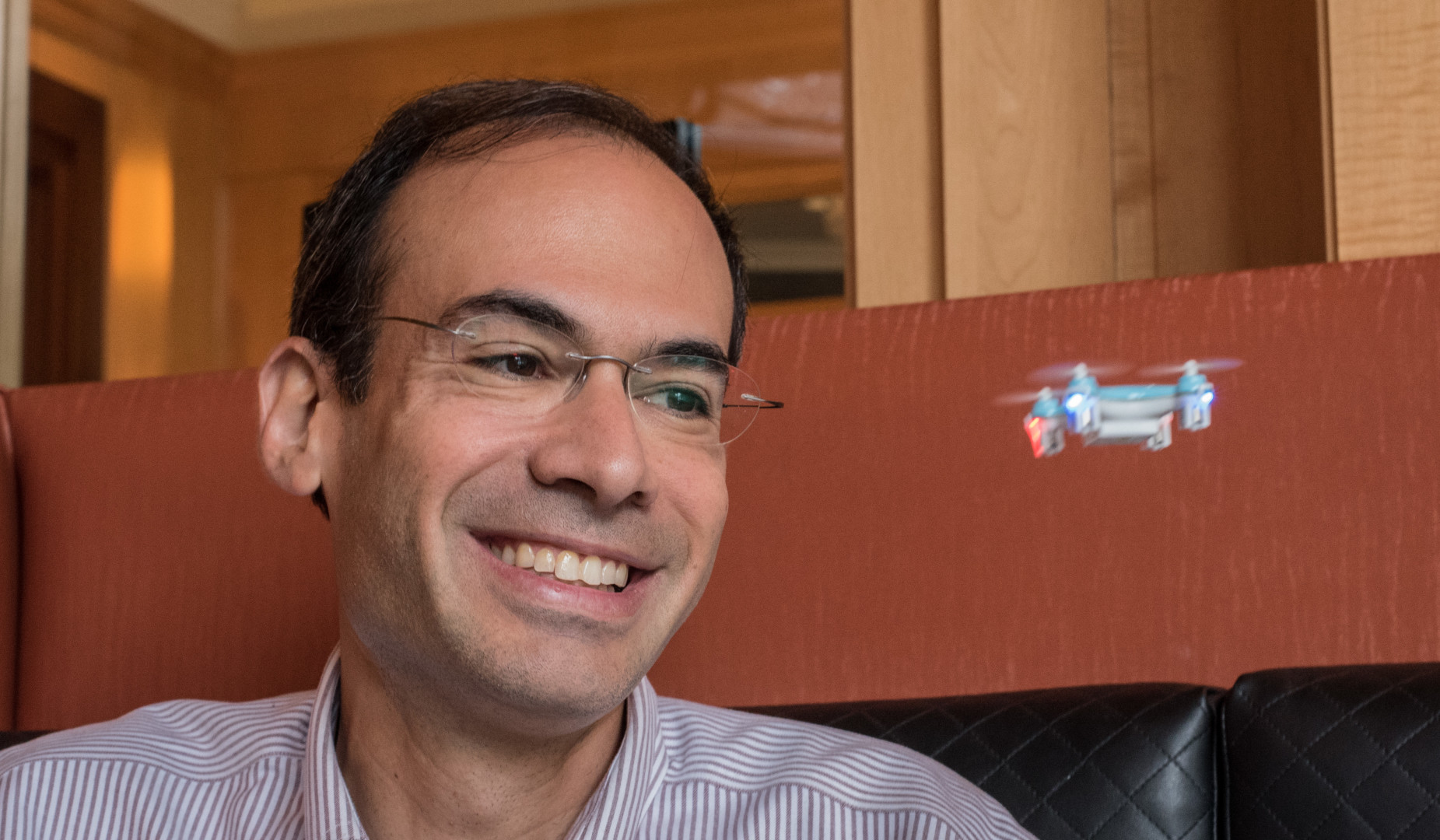

This is where Schulman, usually cool and reserved behind rimless glasses, gets a little heated. “Flying around for 10 minutes, they can learn more than 100 guys on the ground. They can get images that you can study closely.” They’re humanitarians, he said, and they’re using the technology for good.

“It’s an amazing organization, but they were being told to stop,” he said.

The problem with most FAA regulations, Schulman said, is that they revolve around the conventional definition of aircraft – metal tubes full of people and combustible fuel shooting through the sky. Founded after two passenger liners collided over the Grand Canyon in 1956, the agency has risk aversion coded into its DNA. It’s no surprise that the prospect of a sky full of picture-snapping, package-carrying UAS gives the agency pause.

Also pausing? The Department of Homeland Security, which hosted a conference on weaponized consumer drones in early 2015. On exhibit: The DJI Phantom 2 quad-copter rigged with three pounds of mock explosive.

Last February, an intoxicated employee of the National Geospatial intelligence Agency crashed his DJI Phantom on the White House lawn. Coming 10 days after the Homeland conference (originally reported by Wired), the accident caused alarm. If a drunken hobbyist could accidently float a drone over the fence, what could somebody do intentionally?

In response, DJI released a mandatory update for all of its drones, disabling them from taking off within 15.5 miles of the capitol. DJI had been using these “geo-fences” for years to keep its UAS away from airports; at 1.5 miles away, the aircraft will gently land and refuse to take off again.

“We don’t know how many bad headlines we’ve prevented with that,” Schulman said. Last month, Sen. Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) last month introduced an amendment to the FAA’s must-pass reauthorization to require all drone manufacturers to build geo-fencing into their UAS.

While Schulman is proud of DJI for being proactive, he’s a little bitter. “There’s no other technology that has a mandate to not function in a geographical location,” he said. “There’s no requirement that a car turn off when it’s on a sidewalk. Cars don’t even have a hard speed limit. My car goes to 160. There’s no road in the country where it’s legal to go 160.”

While Schumer tries to legislate drone safety, the FAA is currently accepting comments for a proposed rule governing UAS flight – for commercial purposes and otherwise. Among the stipulations: UAS could be no heavier than 55 pounds, would be restricted to daytime flight, and operators would have to pass muster with the Transportation Security Administration. FAA spokesman Les Dorr said the agency has received more than 4,500 comments.

Schulman said the rules apply to companies seeking attempting air freight, like Amazon – not hobbyists. He’s lobbying the FAA to exempt “micro-UAS” – drones lighter than 4.4 pounds, like the DJI Phantom – from the rules. If you have a micro-UAS, Schulman said, “You should be free to do anything. Whether you call it commercial, volunteer or recreational, you shouldn’t need the level of approval that someone flying a 54-pound drone in a more complicated environment requires.”

Dorr said the micro-UAS proposal was among the comments received, and that Schulman and others could expect a finalized rule late next spring. He also pushed back against the concept that the development of unmanned aerial technology was outpacing the government’s ability to regulate it: “We don’t think we’re lagging behind. What we tried to do with the proposed rule was to provide a flexible framework that would accommodate what’s being use today, and what may be used in the future.”

He turned the tables around, saying UAS manufacturers still had progress to make in improving safety features. “There are technologies that still have to be developed – namely detect-and-avoid, and a more robust command and control technology than what exists now for hobby drones,” he said. He said he’s heard of geo-fencing, but declined to comment further.

Schulman isn’t blind to the potential hazards presented by an unchecked explosion in UAS flight, and he’s sympathetic to public concern. But if the FAA responds too strongly to public emotion – that is, if they embrace the “drone” over the UAS – Schulman worries it will kill innovations before they’re fully realized.

“Here’s what’s crucial for me,” he said. “If you had tried to regulate internet problems in the mid-90s, you would have gotten it wrong. You would have stifled innovation. You wouldn’t have Google or Amazon or eBay, any of the real pioneers.”

For example, the agency currently requires UAS operators to maintain visual contact with their aircraft at all times. It also limits operators to controlling a single drone. These strictures preclude Amazon’s grand plan to speed packages to doorsteps, Schulman said: “You just can’t scale the benefits of delivery if you have to have one person control the drone throughout its flight.”

Flight used to be about a person in a cockpit, Schulman said – and that’s no longer strictly the case. Now people are using UAS to shoot videos, map terrain and rescue each other.

“They’re doing amazing things,” he said. “They’re going to save lives. And it’s really important not to hold that back because of legacy regulatory frameworks, or misunderstandings about what the technology can do.”

Update: This story was updated to correct the name of the Federal Aviation Administration.