A widely popular email privacy bill is being held up in a key Senate committee as a lead co-sponsor attempts to hammer out language to leave some wiggle room for counterterrorism.

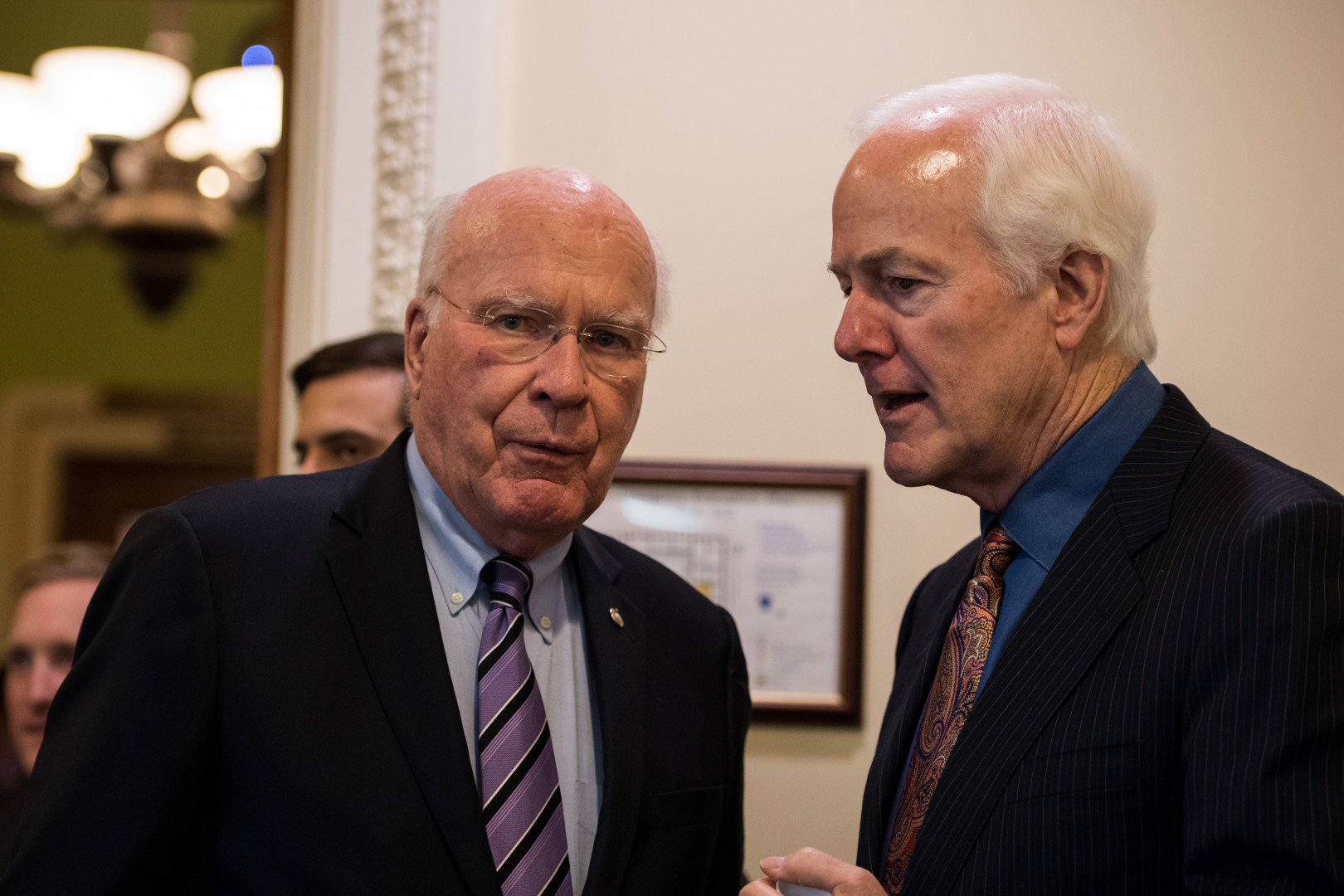

The measure was set for a vote from the Senate Judiciary Committee on Thursday, but the bill’s sponsors requested a delay until a later date so the panel can address concerns raised by some senators. Senate Majority Whip John Cornyn (R-Texas), a co-sponsor, explained his reasoning.

“I fully support the warrant-for-content standard that this bill requires, but in order for this bill to actually become law, it’s got to reflect the interest of all stakeholders,” Cornyn said at the committee meeting. “These are things I hope we can work out, and now that we have a little bit more time, I’m hopeful we can.”

Judiciary Committee Chairman Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) said he is ready to move forward with the long-stalled bill as soon as the committee is good to go. It would update the 1986 Electronic Communications Privacy Act to require law enforcement to get a warrant before compelling an internet service provider to allow access to the content of an individuals’ online communications older than 180 days or stored in a cloud service. In the early days of the internet, those messages were thought to be abandoned.

Still to be resolved are two possible changes that would clarify the ability of intelligence agencies to conduct counterterrorism operations and protect individuals in emergency situations.

Cornyn filed two amendments to address these concerns. The first would clarify that the director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, or someone acting in that capacity, may compel a provider to hand over the name, physical address, email, telephone number and other identifying information if it’s relevant to an authorized counterterrorism operation.

Although this proposal could raise questions, the amendment does clarify that the FBI would not be able to demand the content of any communications. That would keep the bill’s “warrant-for-content” standard intact.

It also avoids a key change that tech and privacy advocates are adamant cannot happen — exempting civil law enforcement agencies from the warrant requirement. This week, Apple and Facebook joined a plethora of civil liberties and tech groups urging the committee to avoid any legal carveouts given to agencies like the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Federal Trade Commission. Both agencies have said that the warrant requirement could hamper their ability to investigate white-collar crimes such as fraud.

Cornyn’s second amendment would allow Americans to give consent for law enforcement to search the contents of their communications, which he said could be crucial in emergency situations. “For example, when someone’s daughter is kidnapped by a human trafficking ring, as recently happened in Houston, and a father wants to go to police to get information to get his daughter back, that he can consent to the access to the information,” Cornyn said.

The bill’s biggest supporters on the committee — sponsor Sen. Mike Lee (R-Utah) and committee ranking member Pat. Leahy (D-Vt.) — have fought for the policy change for the past five years. The committee has favorably reported the bill twice in that time and currently, nine Senate Judiciary Committee members are cosponsors.

The difference now is there is a clear path for this policy to become law. The House passed a companion version of the bill with a resounding 419-0 vote in late April. Now, its Senate supporters want to ensure they can see it over the finish line.

“We see that some of our members on this side of the Capitol have some concerns and I look forward to taking the next few weeks to work with them to resolve those concerns,” Lee said at the executive meeting, after touting the “difficult” task of achieving a unanimous House approval.

There are already a few other amendments on tap. Alabama Sen. Jeff Sessions (R) filed an amendment similar to Cornyn’s that would allow police to compel the content of an individual’s communications if they receive consent from the person who sent it, received it, or was intended to receive it. The amendment goes further than Cornyn’s and would allow representatives of the government to demand the content of communications if they “reasonably” certify that someone risks death or serious physical injury without the disclosure of the communications’ content.

Republican Sens. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina and Jeff Flake of Arizona also submitted amendments. Graham’s amendment, offered with Democratic Sens. Sheldon Whitehouse of Rhode Island and Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut, focuses on enabling the federal government to go after “botnets,” the name given to computers programmed to forward malware to other computers, most of the time unbeknownst to the computer’s owner.

Flake submitted an amendment that would require providers to disclose information that would be privy to orders, subpoenas, and other legal directives.