July 6, 2017 at 3:25 pm ET

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share on LinkedIn

- E-mail to a friend

Supporters of carbon capture technology have pinned their hopes on applying the novel process to energy production in order to boost jobs and make coal more competitive in a lower-carbon future.

But recent commercial setbacks and a lack of government incentives show so-called “clean coal” may not be ready for prime time, analysts say. Instead, it might make more economic sense to apply carbon capture to industrial processes that create a dense amount of carbon dioxide, such as ethanol or fertilizer production.

The process of carbon capture and storage takes carbon dioxide and injects it underground in order to prevent emissions from leaking into the atmosphere. Investment in the new — and therefore potentially risky — technology could support jobs in the coal industry. People in the industry and some lawmakers have pushed for creating incentives for investment.

But the technology has been slowed down by other parts of the coal combustion process, most recently after Southern Co.’s Kemper plant in Mississippi last week was forced to put its clean coal efforts on hold and switch to natural gas due to economic difficulties in scaling up some of the technology.

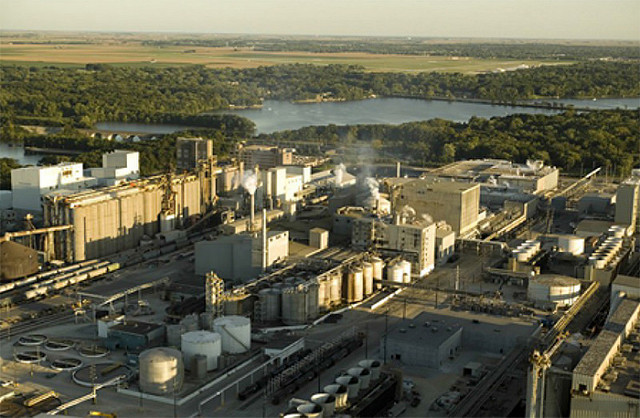

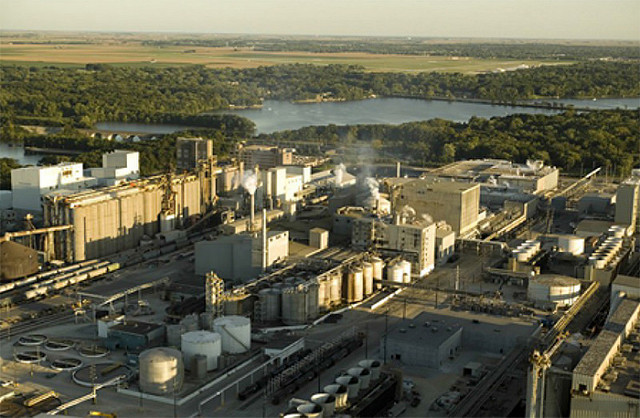

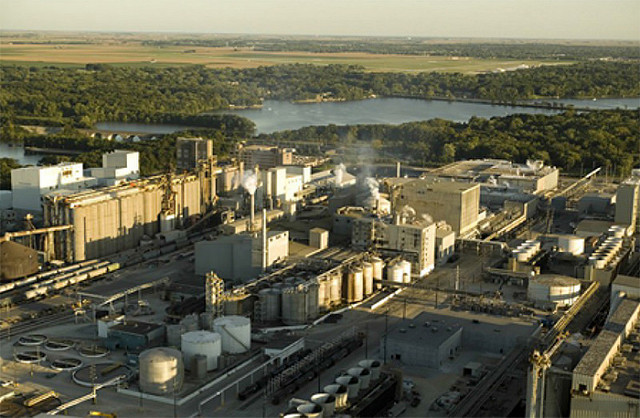

The technology has had more commercial success in other areas, including fertilizer, ethanol and hydrogen production and natural gas processing.

The process of producing ethanol, which is used in motor fuel, can yield more than 98 percent of carbon dioxide, said Ron Munson, the global lead for capture at the Global CCS Institute, a membership group that aims to spur adoption of the technology worldwide.

The Environmental Protection Agency on Wednesday proposed maintaining the current 15 billion gallons of mandated ethanol supply for the 2018 Renewable Fuel Standards, creating a significant potential for captured carbon.

Hydrogen production that uses steam-methane reforming produces a high-pressure stream of gas that yields more than 20 percent carbon dioxide. That compares to a 12- to 15-percent carbon dioxide yield from the coal combustion process at low pressure, which is more difficult and expensive to capture, Munson said.

“The economics make the most sense right now in industrial systems,” he said in an interview Thursday. “The higher carbon dioxide concentration sources are going to be the ones that make the most sense first in terms of [carbon capture and storage] applications.”

Carbon capture technology lacks the incentives and support that governments have given to the renewable energy sector, according to World Coal Association CEO Benjamin Sporton.

“All low-emissions technologies need to be treated equally — this includes [carbon capture]. The only reason why we see the success of renewables is because of the huge and ongoing support from various governments,” Sporton said in a statement Thursday.

The Department of Energy has an entire office dedicated to renewables — the $2.1-billion Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy office — while carbon capture is a smaller part of research at the Office of Fossil Energy, which received less than $1 billion in funding this fiscal year.

On the other hand, supporters of clean coal argue the failed Mississippi plan from Southern Co. should not serve as the test case for the technology because it relied on more complicated coal gasification, not the typical combustion power generators that burn coal for electricity.

“One project not moving forward, especially when it isn’t because of problems related to carbon capture technology, shouldn’t act as a signal that carbon capture doesn’t have a future or that there shouldn’t be more incentives for carbon capture,” Erin Burns, clean energy policy adviser for the progressive advocacy group Third Way, said last week in an interview.

She pointed to NRG Energy Inc.’s PetraNova project in Texas as an example of a clean coal plant that opened on budget and on time, in January 2017. PetraNova captures carbon dioxide emitted post-combustion, operating as a standard combustion rate power plant.

Skeptics of carbon capture, such as David Schlissel, director of resource planning analysis at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, say PetraNova is too new to be considered a reliable and effective use of ratepayers’ money.

Schlissel also testified against Southern Co. for their Kemper plan, opposing the high cost from developing the technology with ratepayers footing the bill.

“You can’t base your energy future on something that hasn’t been proven to work economically,” Schlissel said in an interview Thursday.

This story has been updated to clarify Munson’s comments on hydrogen production.