November 1, 2017 at 3:02 pm ET

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share on LinkedIn

- E-mail to a friend

This year has shown signs of an increased appetite among the rank-and-file in Congress for addressing the issue.

A House proposal to repeal the 2001 AUMF made it through committee but was stripped out by GOP leaders, preventing a floor vote on the measure.

The Oct. 4 ambush in Niger that left four U.S. soldiers dead revived the debate over Congress’ role in authorizing military operations as part of the war on terror, but a new Morning Consult/Politico survey indicates tepid responses from the public on the subject.

U.S. armed forces abroad have been operating under the 2001 Authorization for the Use of Military Force, which Congress passed in response to the Sept. 11 attacks. The bill authorized President George W. Bush’s administration to wage war on those associated with terrorist attacks, namely al-Qaida, but it also extended to other Islamic militant groups. Subsequent administrations have cited the AUMF to legally justify engaging in conflicts without declarations of war or other congressional consent.

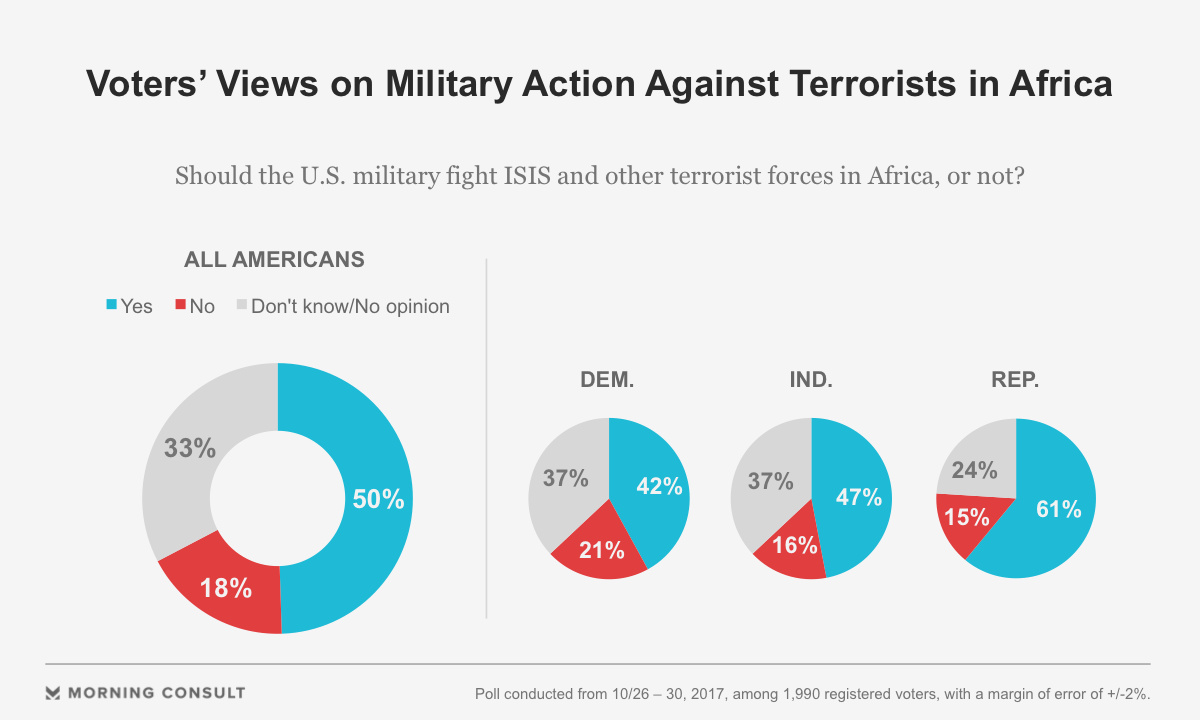

The Trump administration recently identified 17 counties, mostly in Africa and the Middle East, where U.S. military personnel are deployed, Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Bob Corker (R-Tenn.) said at the panel’s latest hearing on war authorization, on Monday.

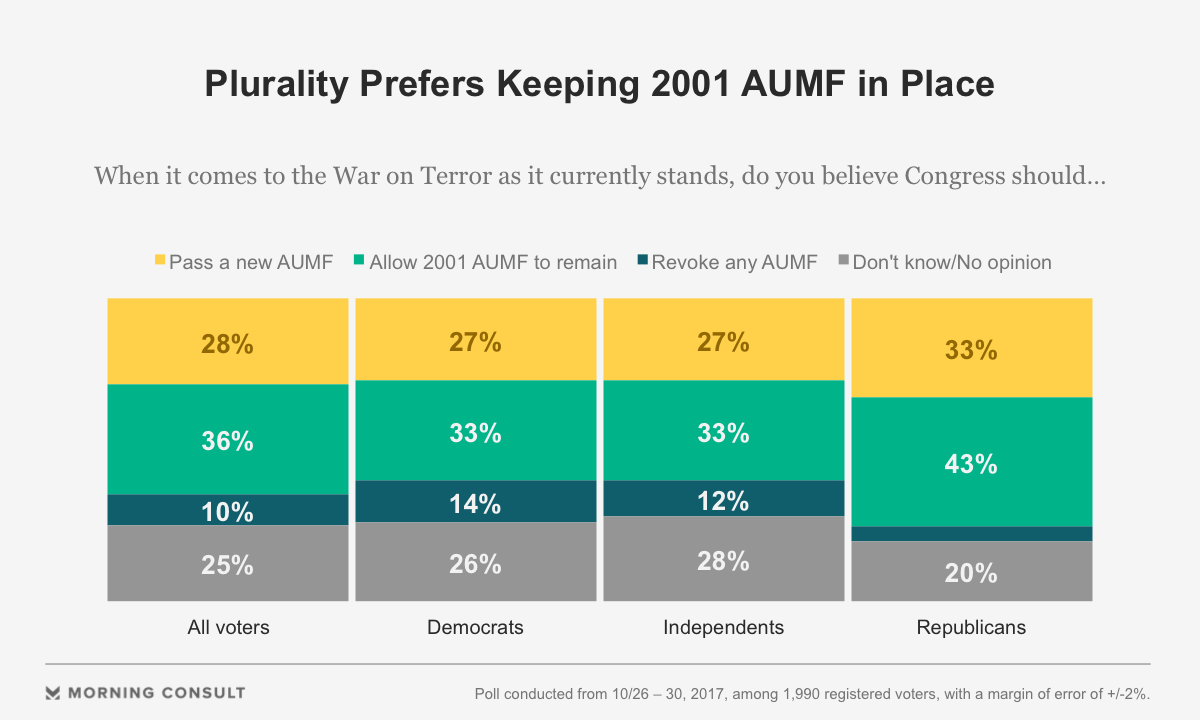

Critics of the 2001 AUMF say it’s time for federal legislators to assert their powers and draft a new authorization. But in an online survey conducted Oct. 26-30, a 36-percent plurality of respondents said Congress should allow the 2001 authorization to remain in place.

The national survey of 1,990 registered voters, which has a margin of error of 2 percentage points, showed 10 percent support revoking the current AUMF without a replacement, while 28 percent said Congress should pass a new AUMF and 25 percent said they didn’t know or had no opinion. Proponents of drafting a new war authorization say those numbers reflect a lack of awareness and recognition among the general public for the arguments used to put U.S. forces in harm’s way — and a failure of congressional oversight.

“The public indecisiveness is a function of the Congress defaulting on its constitutionally prescribed role,” Michael Glennon, an international law professor at The Fletcher School at Tufts University who as a Senate lawyer in 1973 helped draft the War Powers Resolution, said in an Oct. 31 phone interview. Glennon noted that Vietnam-era hearings helmed by then-Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman William Fulbright (D-Ark.) were instrumental in educating the public and, ultimately, hamstringing the executive branch’s power to wage war unilaterally.

Critics of the Defense Department’s ongoing use of the 2001 AUMF also say the declining share of Americans who serve in the armed forces contributes to a lack of public awareness. In a briefing with reporters at the Capitol on Monday, Sen. Chris Coons (D-Del.), a Foreign Relations Committee member, said that because roughly 1 percent of American households have a family member currently serving overseas, there’s a lesser sense of urgency on the state of military deployments.

“Recent weeks make it clearer than ever that we need a new authorization,” Coons said, adding that the continued sprouting of groups claiming affiliation with the Islamic State terror group, such as the group responsible for the Niger attack, “have exceeded the attention of the average American and possibly the average senator.”

Sen. Jeff Flake (R-Ariz.), who sits on the Foreign Relations panel, introduced a joint resolution on May 25 that would authorize the fight against ISIS and other terrorist groups for a period of five years while providing an expedited reauthorization process prior to its expiration. Sen. Tim Kaine (D-Va.), a fellow member of the Foreign Relations Committee, is the lone co-sponsor.

During Monday’s committee hearing, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and Defense Secretary James Mattis said any new AUMF shouldn’t include time or geographical constraints, and should also be passed before repealing the 2001 authorization.

This year has shown signs of an increased appetite among the rank-and-file in Congress for addressing the issue. On June 29, the House Appropriations Committee adopted an amendment offered by Rep. Barbara Lee (D-Calif.) to the fiscal year 2018 defense appropriations bill that would have repealed the 2001 AUMF — although it was stripped out by GOP leaders before it reached the floor of the full chamber. That was the first time the panel adopted the amendment, which had been offered in previous years.

Coons said he understands congressional leaders’ concern “that we won’t be able to come to a consensus” on a new authorization, potentially endangering U.S. troops. But, he noted, “Congress has ceded too much of a role and responsibility.”

Glennon said the abdication of Congress’ role in war authorization is a reflection of political concerns, particularly following the electoral fallout from the U.S. occupation of Iraq last decade, which helped Democrats sweep into power in 2006 and 2008, but also cost former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in her presidential bids.

“Members of Congress have every incentive to avoid casting a vote on a potentially career-ending issue,” he said. “They continue to say publicly that they think Congress should step up to the plate, and then proceed behind the scenes to do everything possible to avoid having to take a position.”