A month after Republicans won control of the United States Senate last year, Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) told a reporter the new majority would “make every effort we can” to repeal the Affordable Care Act.

But after nine months of a Republican Congress, President Obama’s signature domestic achievement remains the law of the land. Conservative activists and their allies in Congress have turned their animus from the president who passed the ACA to the Republican leaders who have, so far, been unable to repeal it.

“Every effort,” to McConnell, meant something very different than it did to those conservative activists.

Those activists increasingly believe Republican leaders on Capitol Hill have failed to win any concessions from the president they loathe, whether it’s funding for Planned Parenthood, reductions in spending, the Environmental Protection Agency’s new rules on power plants, or a host of other initiatives. Thanks to long-standing Senate rules that allow the minority party to block legislation, Obama hasn’t even had to use his veto pen to defend his legacy. The expectations Republicans set for their own voters if they won back control of the House and Senate have gone almost entirely unmet.

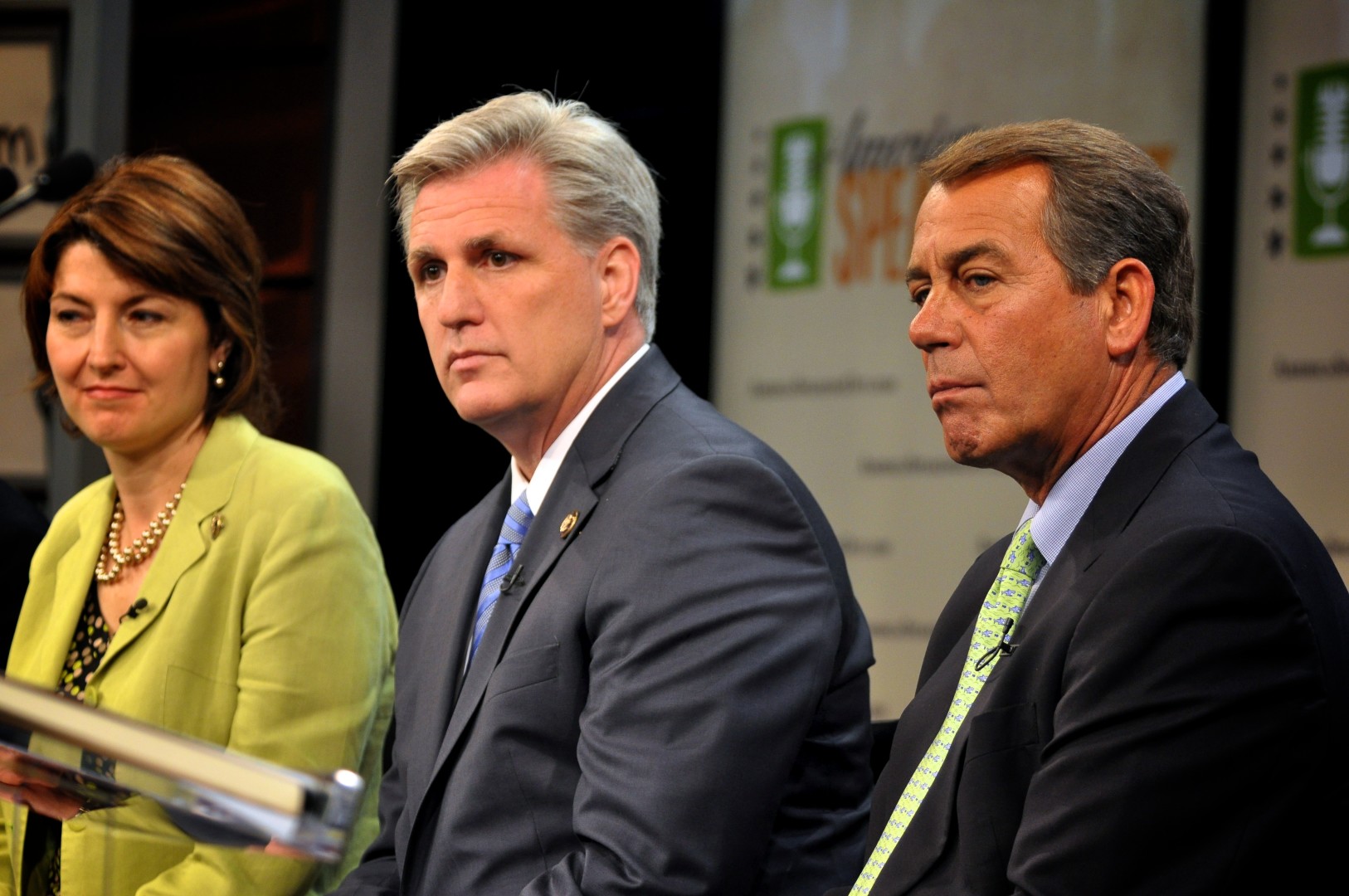

Frustration with those expectations boiled over last month, when House Speaker John Boehner realized his future atop a fracturous Republican conference was untenable. It bubbled up again Thursday, when Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) pulled out of the race to replace Boehner, after several of his closest allies were bombarded by constituents demanding they oppose McCarthy.

And it threatens to undermine any future speaker — even someone almost universally loved within the House GOP, like Rep. Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) — almost immediately.

“I’m not sure there is much McCarthy or Boehner could have done” to save themselves, said one Republican who helped elect the wave of Tea Partiers in 2010. “Boehner was able to outmaneuver [conservatives] for a long time, but he was out of options by the end. McCarthy was never going to be able to master how to pull on the levers of power within the House.”

For months, Republican leaders have pleaded for understanding. The rules in place, after all, prevent Democrats from running roughshod over Republicans when the majority is reversed. With 46 members of the Democratic caucus standing in Republicans’ way in the Senate, and the very fact that Obama has a pen with which to veto legislation, political reality stands in the GOP’s way.

Here’s how McConnell put it, in that December interview: “It is a statement to the obvious, however, that Obama — of Obamacare — is the President of the United States, so I don’t want people to have [unrealistic] expectations about what may actually become law with Obama — of Obamacare — in the White House.”

But the obvious political reality is no longer good enough for the conservative base, most of whom do not believe their party’s leaders in Washington are trying hard enough. Acknowledging the hurdles Obama and Senate Democrats represent, they feel, is tantamount to surrender. If the rules need to be changed to advance the conservative cause, the logic goes, then change the rules. If the government needs to be shut down to force concessions from Obama, then shut the government down.

This all-or-nothing strategy demanded by newer conservative members also represents a generational divide between younger Republicans elected to Congress in the wave elections of 2010 and 2014 and the leaders who helped get them elected, chiefly Boehner, McCarthy and McConnell.

The leaders, steeped in the political ebbs and flows of Washington, are content to win minor concessions today in pursuit of larger victories tomorrow. They are more comfortable addressing the Chamber of Commerce than they are a rally of Tea Party activists.

The newer generation is determined to score major wins in the short term, driven by pressing fears of the ramifications of Obama’s actions. They do not entirely trust the Chamber of Commerce — as illustrated by conservative opposition to reauthorizing the Export-Import Bank, a major chamber priority — and they owe their political careers to those Tea Party activists.

Today’s leaders “are incrementalists by nature,” says one Republican strategist who spent Thursday on the phone with nervous donors. “Our voter base doesn’t think you can save this country incrementally.”

McConnell, surrounded by a Republican conference made up of institutionalists, is beyond the reach of conservative frustration with the pace of change. Boehner and McCarthy had to deal with a much more substantial, much more intractable conservative faction. The length of the next speaker’s tenure will be determined largely by how long he or she maintains credibility with that conservative faction.