April 1, 2016 at 5:00 am ET

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share on LinkedIn

- E-mail to a friend

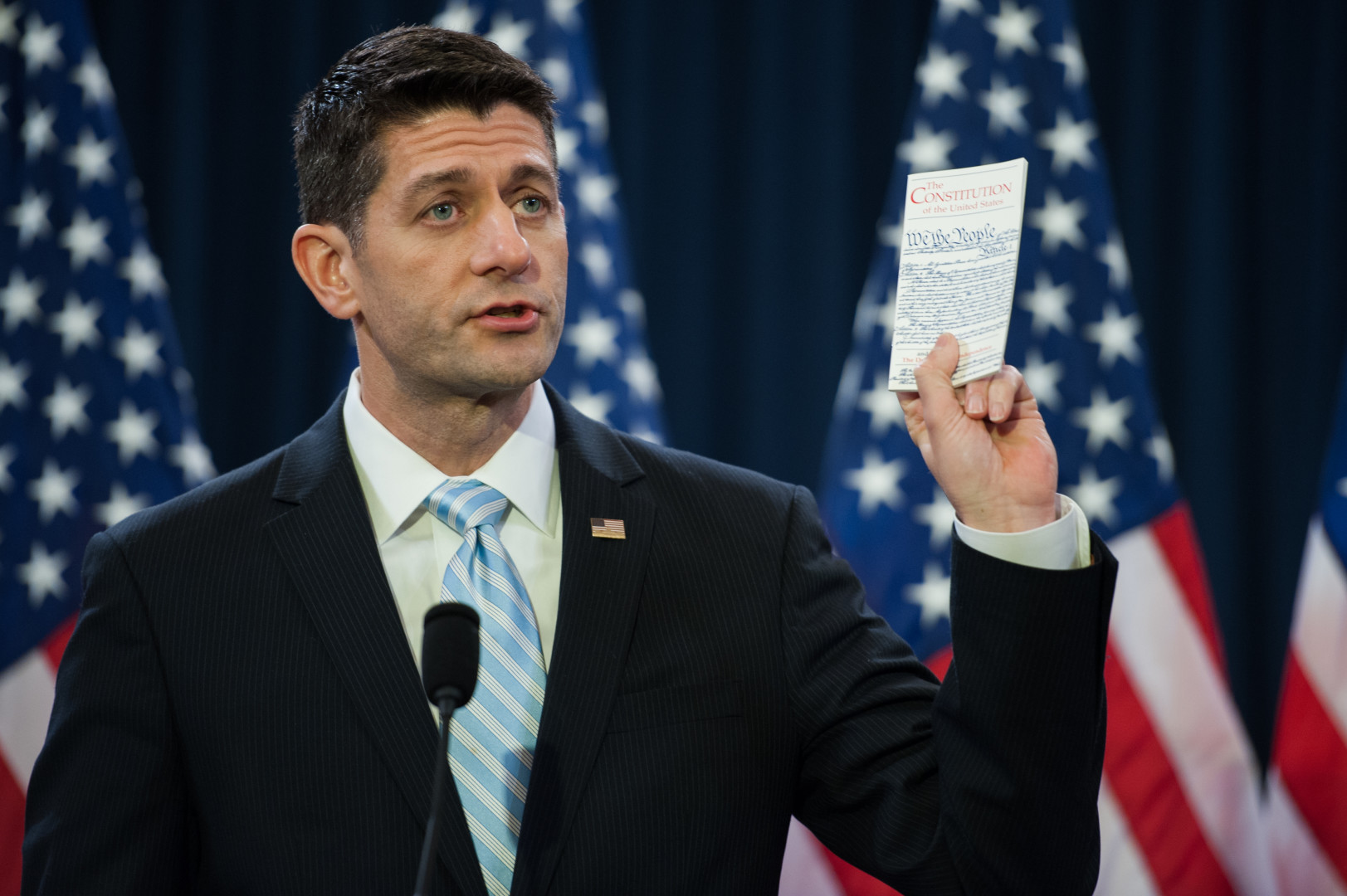

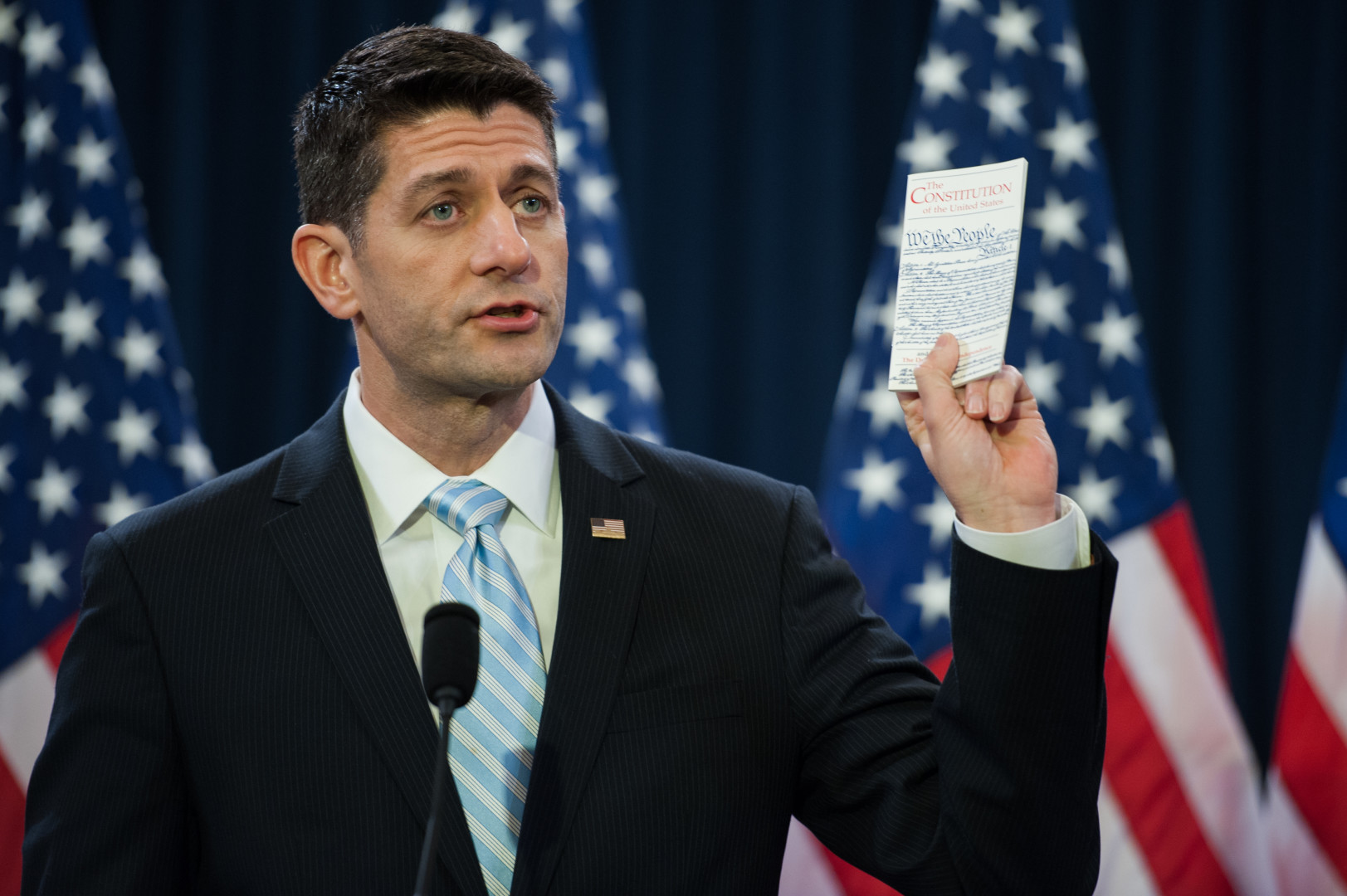

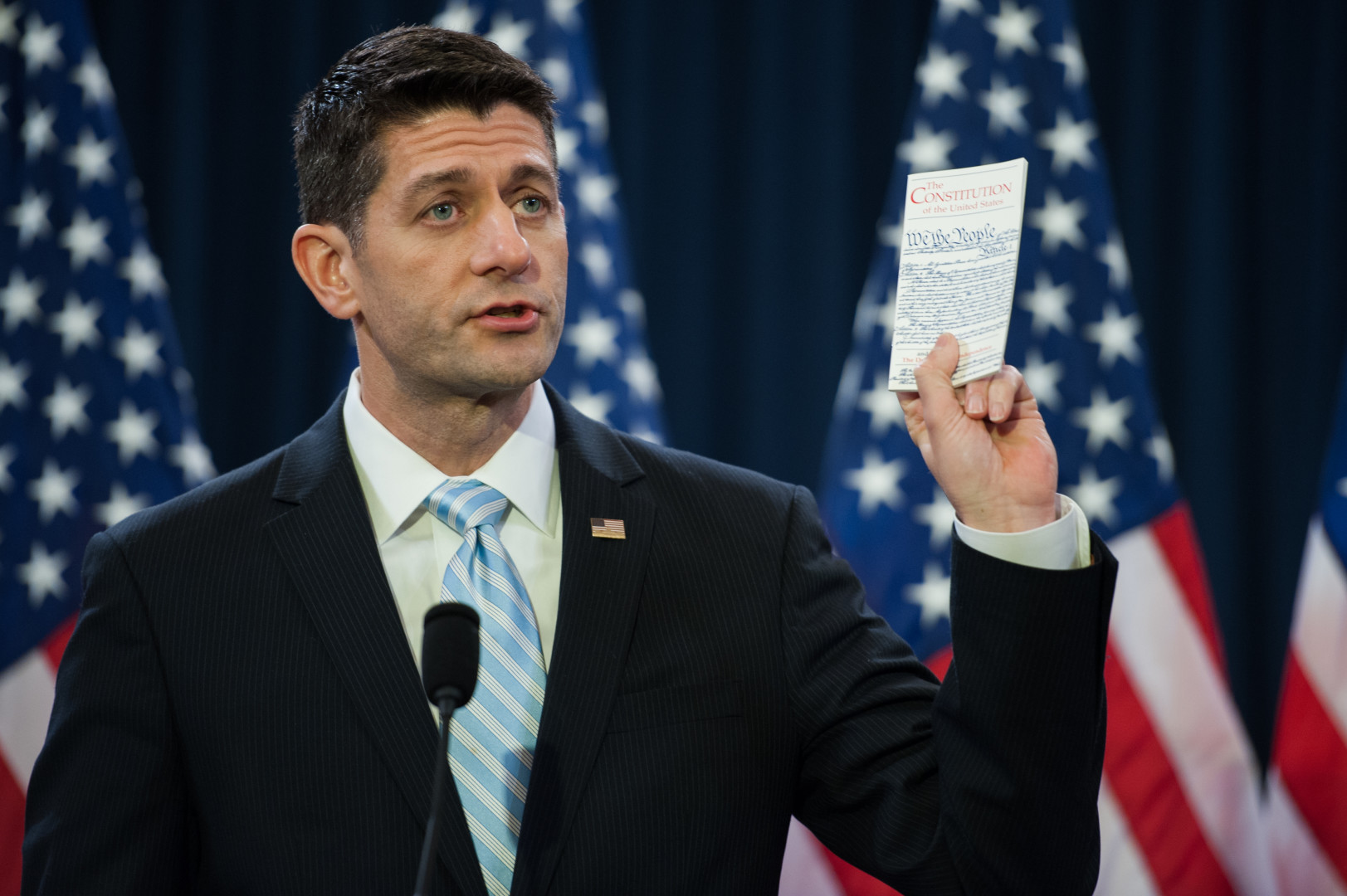

Paul Ryan ascended to the House speakership pledging a departure from the leadership styles of the past. Gone would be the punitive measures for Republicans who broke ranks on procedural votes. Ryan would give more rank-and-file members input into the legislative process, restoring committee independence and opening up major bills to a wide array of floor amendments.

Most of all, he promised to talk straight. No more extravagant promises that Republicans would be able to repeal Obamacare while President Obama sat in the White House. That’s a departure from his predecessor, John Boehner (R-Ohio). Conservative members complained that Boehner made a habit of promising the moon and the stars when he knew neither were within House Republicans’ grasp.

There is an irony to Ryan’s commitment to setting realistic expectations. He played a critical role during Boehner’s reign in encouraging Republicans to outline ambitious policy goals. As the top Republican on the House Budget Committee from 2007 to 2014, Ryan presided over a transformation of congressional budget resolutions. They went from documents intended to enable realistic governing to aspirational proposals that set aside what is politically feasible in favor of visionary, sometimes fantastic, policy proposals.

Ryan’s efforts to be realistic as speaker have won him consistent plaudits from the upstart conservatives who toppled his predecessor. He has so far avoided the acrimonious relationship with the House Freedom Caucus that led North Carolina Rep. Mark Meadows to file a motion to depose his own party’s speaker. Even as House conservatives bemoan a budget at a $1.07 trillion spending level that Ryan supports, they still applaud his dedication to searching for consensus.

But Ryan’s budget transformations live on, and they are causing the same problems they caused for his predecessor.

“I do think the Ryan budgets reflected a shift in focus of budget from governing document to a vision document,” said Ed Lorenzen, a senior advisor at the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. “The result has been that budget resolutions assume major policy changes with no expectation that Congress would actually take action on legislation making those policy changes.”

Ryan was, in other words, fully immersed in focusing his party’s gaze on ideas that stood little chance of being enacted.

That’s not necessarily a critique. In Washington, vision is a powerful thing. Nobody doubts that Ryan’s tenure on the budget panel powerfully shaped how Republicans conceive of themselves. And Democrats are already worried Ryan’s ability to channel his party’s disparate energies could prove dangerous, particularly in the agenda program he is spearheading for the House GOP conference later this spring.

Ryan has also demonstrated an ability to make deals. As the Budget chairman, he worked with Senate counterpart Patty Murray (D-Wash.) in 2013 to strike a budget deal in the height of Washington partisanship. More recently, he successfully steered legislation through Congress granting Obama fast-track trade authority for a then-incomplete Pacific free trade agreement. That trade deal, the Trans-Pacific Partnership, has since concluded and appears to face serious opposition in both parties.

Yet in reshaping the GOP’s policy platform from his budget perch, Ryan changed the very nature of congressional budget resolutions. He removed budgets from the immediate political moment, allowing for ambitious policy proposals that have become central to his party’s identity. But the changes also reduced the ability for budget resolutions to guide legislators’ lawmaking.

“The congressional budget resolution can be a real governing document when there is the political will to follow through on the assumptions in the budget,” Lorenzen said. “But when it becomes a vision document setting out ambitious goals disconnected from what Congress is willing and planning to do in actual legislation, it becomes meaningless.

The current congressional budget framework was established by the Congressional Budget Act of 1974. It sought to impose some discipline on the legislative branch’s spending habits by forcing lawmakers to settle on fiscal targets and establish some enforcement mechanisms to achieve those targets.

Even though budget resolutions technically never become law, they theoretically serve important functions in the annual appropriations process. They set top-level spending limits, allocate the funding among the 12 subcommittees that write federal spending bills, and project spending targets for the next five or 10 years. But there are ways around all of these benchmarks and years when Congress doesn’t complete a budget. Everyone survives.

Capitol Hill budgeters used to take the budget’s fiscal projections more seriously. “They did actually do it in the Clinton administration,” said Alice Rivlin, the founding director of the Congressional Budget Office and the director of the Office and Management and Budget under President Bill Clinton. “In the nineties, it worked very well.”

“It wasn’t all process. People will tell you, quite rightly, that an important part of the improvement in the budget was the economy was very strong in the second half of the nineties and that the defense budget, as a result of the end of the Cold War, would have probably gone down anyway,” she continued. “But the process certainly helped.”

Marc Goldwein, another CRFB budget guru who served as a senior analyst on the so-called Super Committee in 2011, said budget targets have always been an ideal. But not so long ago lawmakers actually attempted to meet those targets.

“In the past, Congress actually tried to follow the budget resolution by passing legislation to reflect it. They didn’t always end up with exactly what they proposed, but that was the goal and they worked toward getting as close as possible,” he said.

Ryan changed the game when he took up the committee’s gavel in 2010. Paul Winfree, the director of the Heritage Foundation’s Institute for Economic Policy Studies, said Ryan made two significant changes to GOP budgets.

“First, budgets written under his chairmanship took balancing the budget seriously in a time when addressing the deficit looked insurmountable,” he said. “The second difference is that Ryan’s budgets proposed fundamental changes to the structure of Medicare to improve long-run sustainability without overly focusing on the short-term financial aspects of the reforms.”

House GOP budgets since have followed Ryan’s lead.

Balancing the budget within 10 years has essentially become a requirement of Republican budget resolutions in the House, regardless of the size of the deficit. It’s now standard practice to assume Herculean political feats, such as the complete repeal of Obamacare, that have no chance of happening without a Republican in the White House. Budgets are now in effect messaging documents, and many members assume they will play little role in determining what legislation actually makes it through Congress.

Last year’s concurrent budget resolution, the first in years, provides an example of just how little bearing the budget has on actual legislating. It called for more than $5 trillion in deficit reduction over 10 years. By the end of 2015, the deficit was instead projected to grow, the result of a budget deal and spending-tax package that completely disregarded the GOP budget plan.

Still, budget experts on both sides of the aisle said Ryan was not setting budgetary precedents in a vacuum. “It’s fair to say that he presided over a change. Though I would also say that Ryan was responding to the times,” said Winfree.

“The Ryan budgets reflected a very conservative, small government view,” said Rivlin. “The makeup of the Republican Party in the Congress changed to the right. He was reflecting that.”

And ultimately, she suggested, the shifting purpose of a budget resolution might be less important than the gridlock that has ground all legislating to a halt. “Process isn’t the problem,” concluded Rivlin. “The Congress has broken down. It’s totally polarized. They aren’t doing policy, any kind of policy.”

Nonetheless, Ryan’s innovations as the Budget Committee chairman have played a role in this year’s budget impasse.

At the core of House conservatives’ current opposition to Price’s budget plan is their frustration with the House GOP budget’s status as a largely visionary document. They see lots of policy they like, but no path to making those policies law, towards making them “real,” as House Freedom Caucus Chairman Jim Jordan (R-Ohio) explained to reporters in late March.

“It has to be something real that actually addresses the fiscal environment we find ourselves in,” he said. “Just a vote on something and a promise to fix a rule down the road, those kind of things. We’ve had all those before, and frankly the American people are fed up with that kind of approach.”