After Tuesday’s special election in the 4th District of Kansas, some progressives were irate that House Democrats’ campaign arm did not do more (and sooner) to push long-shot candidate James Thompson across the finish line.

But in the view of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, their involvement in the race might have done more harm than good and proved the point of Republicans backing state Treasurer Ron Estes: that Thompson was the choice of Washington insiders, such as House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.), a favorite Republican villain.

“There were a number of reasons for our level of involvement in Kansas, but ultimately a contest between candidates rather than a contest between national parties was beneficial for James Thompson in a district like this,” Meredith Kelly, a spokeswoman for the DCCC, said in an email. “The race was not nationalized at all until the NRCC rushed in last week, which allowed Thompson to fly under the radar for a while, outwork Estes and develop his own brand.”

Indeed, the national cavalry did not arrive in south central Kansas until the final few days of the contest after a Republican internal poll leaked showing Thompson within a point of Estes in a dark red district. Republicans called on President Donald Trump to tape a robocall and dispatched Texas Sen. Ted Cruz to rally the faithful, prompting Democrats to funnel live calls to the district on Monday and Tuesday — a minimal presence that preceded Thompson’s 7-point loss.

“We were really under the radar until that last week,” said Colin Curtis, a native Kansan who returned from Washington in February to manage Thompson’s race. “I really do think that what kind of killed it for us was the last minute investments by Republicans.”

Despite Thompson’s loss, the relatively tight margin of the Kansas contest — a 20-point swing from Trump’s victory there just five months ago — has Democrats energized about the upcoming special elections to replace lawmakers plucked by Trump to fill administration posts. In the handful of races on the map, strategists said this week that Democrats would do well to keep their distance from making their race parts of a national theme.

“What happens is a congressional race — instead of being a litigation between two candidates — it becomes a litigation between two parties,” said Democratic strategist Jesse Ferguson, the former director of the DCCC’s independent expenditure arm.

“It’s not that the brand is the problem,” Ferguson, who also served on Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign, said of the Democratic Party. “It’s when you engage in a partisan back-and-forth between two parties instead of two candidates, you do make it harder for the candidate to break out.”

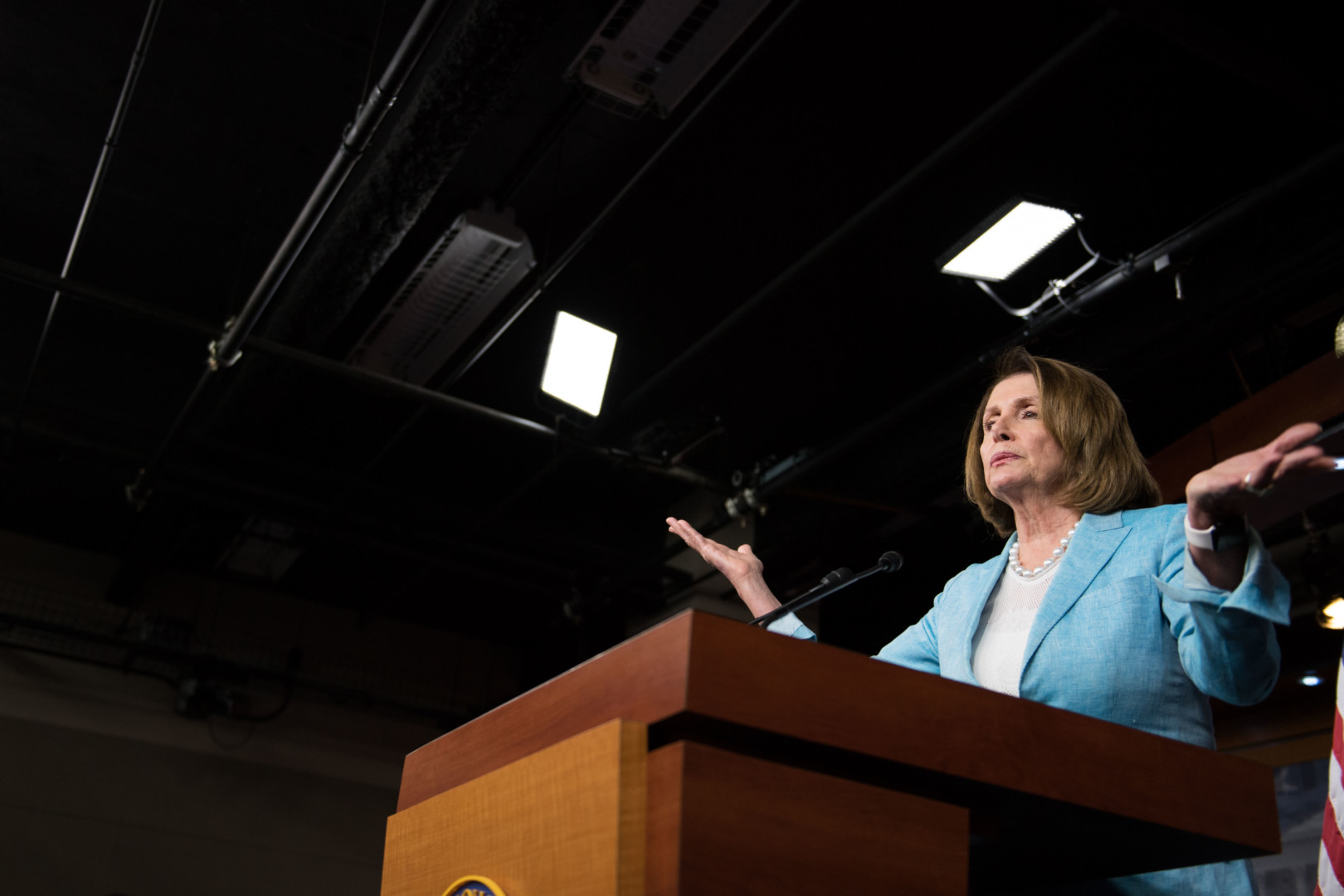

Pelosi has become a fixture in Republican campaign ads, even though more than a third of voters (37 percent), in Morning Consult/POLITICO’s latest survey, said they have never heard of her. She’s more loathed on the right than loved by the left: 44 percent of GOP voters view her unfavorably, compared with 39 percent of Democrats who like her.

In Kansas, and now ahead of Georgia’s special election next week, Republicans have embraced the partisanship, framing the race as more of a defense against a Democratic takeover of Congress and less about a standout Republican candidate. Ferguson said it makes sense.

“If it reverts to its partisan nature, they win,” said Ferguson, who’s currently not affiliated with any company or organization. “If you are a Republican voter and we have a chance of getting you to vote for the Democratic candidate, our chances decrease if you see the race as a proxy battle.”

Democrats have avoided such a proxy battle before. Some who have won in red states, such as Sen. Jon Tester in Montana and Sen. Heidi Heitkamp in North Dakota, were able to localize their races and separate themselves from the national monolith. They did it with the help of national Democratic groups, too – shaking off charges that they would serve as a rubber stamp for then-President Barack Obama’s agenda.

But those races weren’t special elections, and data pointed to them being worthwhile investments for national committees. Ferguson, who has made his share of decisions about where to spend finite campaign resources, said he has been tempted by the shiny object himself, noting the DCCC’s decision to spend in the 2013 special election that ultimately elected Republican Rep. Mark Sanford in South Carolina.

“You have to say, ‘How am I going to feel election night about coming up one district short because we didn’t have the resources for it that we had spent on a long shot?” he said, pointing to the example of Sanford, who defeated Elizabeth Colbert Busch after painting her as another Pelosi. “It wasn’t the wrong decision to spend at the time — the data looked more promising — but we lost by a larger margin than we’d expected. In hindsight, I would have loved to have the money.”

Democrats have been mum about Montana’s special election to replace former Rep. Ryan Zinke, who now leads the Department of the Interior. There, musician Rob Quist is facing Republican businessman Greg Gianforte in a special election next month.

In Georgia, where 6th District candidate Jon Ossoff has become something of a rock star among the liberal base while boasting eye-popping fundraising numbers, some Democratic operatives think taking back Health and Human Services Secretary Tom Price’s seat could be tough. Ossoff will appear on a “jungle” primary ballot Tuesday along with other Republicans and Democrats. If nobody achieves 50 percent of the vote, the top two finishers will head to a runoff in June.

“The good news is we shouldn’t be competing in any of them,” Ferguson said of the special elections. “If you sat down with the seats in the House and mapped out the easiest path to 218, it wouldn’t include any of the seats that have contested special elections.”